| GDV is a condition affecting large, deep-chested breeds |

Gastric dilatation and volvulus (GDV) or ‘bloat’ is not a disease specific to flat-coated retrievers but it is much discussed amongst flat-coat owners as it is more common in large breed dogs and it is a true veterinary emergency. If left untreated a dog with bloat can rapidly die through associated shock. For this reason it is very important that we all learn the signs to look out for so we might improve our dog’s chances of surviving it should it occur.

Anatomy of the stomach

The stomach is part of the long tubular pathway through which the dog’s food passes. It is an expandable, muscle-lined sac containing glands in its walls that produce acid and digestive juices. Food enters the stomach from the oesophagus and exits through the duodenum to pass on to the small intestines.

What causes bloat?

The exact chain of events that leads to a GDV occurring remains unclear. We do know that it becomes more likely by eating a small number of large meals and by eating rapidly. The stomach can dilate as a result of the dog literally swallowing air (‘aerophagia’). The gas is not due to bacterial fermentation of the food.

What happens when a dog bloats?

| A bloated stomach does not always twist (gastric dilation) A twisted stomach does not always bloat (chronic volvulus) |

If the stomach twists it pinches the point where the oesophagus enters, a bit like twisting the top of an inflated balloon. This means that air and food that is in the stomach becomes trapped and the dog can neither belch nor vomit up the contents. A pinch effect at the exit of the stomach also prevents air passing into the intestines.

The onset of clinical signs is usually acute and is often reported to follow a large meal and/or a period of exercise.

Signs to look out for

Call your vet immediately if your dog is displaying the following signs: restlessness, non-productive retching, salivation, abdominal distension (particularly where a hollow, drum-like sound can be made with a tap of the finger), weakness and collapse.

Treatment

If a twist has not occurred then a dog with bloat may occasionally be treated without surgery. Once the dog has been given treatment for shock the vet may x-ray the dog to confirm the diagnosis. It may be possible to pass a stomach tube with the dog conscious (under sedation) allowing air to escape through the tube. Most cases, however, require emergency surgery to decompress the stomach and correct the twist. Once corrected, the stomach may be permanently sutured to the side of the body to prevent a further twist (this is called a gastropexy).

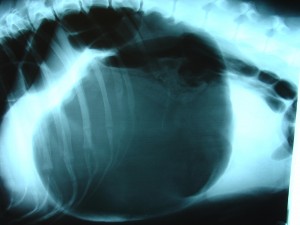

Figure 2- Lateral radiograph of a bloated dog’s abdomen.

The dark, air-filled stomach clearly filling the picture.

Dangers

When the stomach dilates it squeezes the blood vessels in the stomach wall reducing their ability to supply blood to the muscular wall. The stomach is closely associated with the spleen, and a twist of the stomach may also interfere with the supply of blood to the spleen. Delays in treatment for bloat causes the stomach and spleen to be at great risk of necrosis and some dogs may need to have their spleen or a portion of the stomach to be removed.

Once the circulation is re-established there is a further risk to the dog of shock, leading to concern over damage to other body organs, most especially the heart.

Prevention

There have been lots of ideas about why a dog’s stomach bloats. Studies have suggested that the incidence of the condition is higher in older dogs, in fast-eating dogs and in dogs fed from a raised food bowl. We always try to avoid walking or working our dogs just before or just after a meal.

Bearing in mind that I am writing this article for owners of one breed in particular I am pleased to tell you that it has been reported that bloat is notably less common in happier dogs.

Keep those tails wagging!

Chris Hewison BVetMed MRCVS